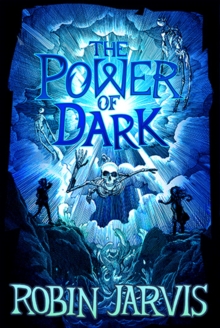

Robin Jarvis writes fantasy and horror for children and teenagers, and The Power of Dark (out on 2 June) is his latest novel. Although I was aware of Robin Jarvis's books, I'm just old enough to have missed out on them as a child, as I was 13 or 14 when his first novel was published, and by that point I was mostly reading books aimed at adults. This is a shame as, judging from The Power of Dark, I would have liked Jarvis's books a lot when I was reading from the 9 - 12 or teen shelves in the library.

Set in Whitby, The Power of Dark is the story of two friends, Verne and Lil, who inadvertently become embroiled in a centuries-old battle involving ancient forces awakened in a terrible storm. Whitby becomes strangely divided, with one half of its population developing a strange obsession with creating eerie mechanical gadgets with a life of their own, and the other half devoting itself to witchcraft and magic, as the legacy of 17th century magician Melchior Pyke, witch Scaur Annie and Pyke's sinister manservant Mister Dark threatens to overwhelm the town.

Set in Whitby, The Power of Dark is the story of two friends, Verne and Lil, who inadvertently become embroiled in a centuries-old battle involving ancient forces awakened in a terrible storm. Whitby becomes strangely divided, with one half of its population developing a strange obsession with creating eerie mechanical gadgets with a life of their own, and the other half devoting itself to witchcraft and magic, as the legacy of 17th century magician Melchior Pyke, witch Scaur Annie and Pyke's sinister manservant Mister Dark threatens to overwhelm the town.

Set in Whitby, The Power of Dark is the story of two friends, Verne and Lil, who inadvertently become embroiled in a centuries-old battle involving ancient forces awakened in a terrible storm. Whitby becomes strangely divided, with one half of its population developing a strange obsession with creating eerie mechanical gadgets with a life of their own, and the other half devoting itself to witchcraft and magic, as the legacy of 17th century magician Melchior Pyke, witch Scaur Annie and Pyke's sinister manservant Mister Dark threatens to overwhelm the town.

Set in Whitby, The Power of Dark is the story of two friends, Verne and Lil, who inadvertently become embroiled in a centuries-old battle involving ancient forces awakened in a terrible storm. Whitby becomes strangely divided, with one half of its population developing a strange obsession with creating eerie mechanical gadgets with a life of their own, and the other half devoting itself to witchcraft and magic, as the legacy of 17th century magician Melchior Pyke, witch Scaur Annie and Pyke's sinister manservant Mister Dark threatens to overwhelm the town.

There are plenty of entertaining scares - there's a particularly memorable moment near the beginning of the book when the storm causes a landslide of skeletons from the church yard directly into Lil's bedroom, and the Mister Dark character is genuinely sinister - but it's not unnecessarily grisly; as befits its target audience it's more the stuff of creepy Halloween fun than violent horror. The book is also very funny at times, particularly for those who know Whitby. Lil's parents are middle-aged goth Wiccans who constantly embarrass their pragmatic, colour-loving daughter, while Verne's family run an amusement arcade and tinker with Victorian automata - indeed, the division of the town is essentially goths versus steampunks, which will certainly elicit a nod of recognition from anyone familiar with Whitby Goth Weekend.

Despite the humour (there's also a running gag about a farting Westie) there are genuinely atmospheric moments too, particularly in some of the flashbacks that Lil and Verne see through their increasingly vivid dreams of Pyke, Annie and Dark - although these don't form the main part of the story, they were actually my favourite part of the book.

I don't think The Power of Dark has quite the 'crossover' appeal of some other children's or YA books I've read - I'm sure adult readers will find it fun and entertaining, as I did, but will probably hanker for something a little more immersive with more complex characters. I would absolutely recommend this one for kids who like horror and the supernatural, though, especially if they also have a sense of humour. It's a great book to curl up with on a stormy night, and it's the first in a series, too, so they can get stuck in knowing there's plenty more to come.

My thanks to the publisher, Egmont, for sending me a copy of this book via NetGalley in return for an honest review.