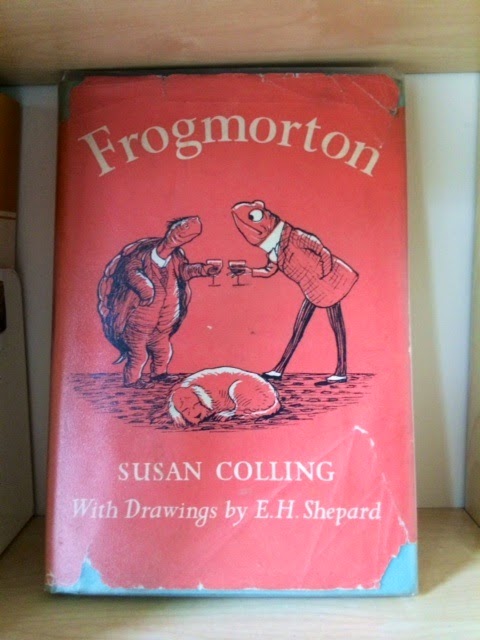

I don't know anyone at all outside my family who has read, or even heard of, Frogmorton by Susan Colling. My mum bought a hardback copy from a jumble sale when we were little. It was published in the mid-50s and has beautiful pen and ink pictures by EH Shepard, famous for producing the iconic illustrations for the Winnie-the-Pooh books and The Wind In The Willows.

I don't know anyone at all outside my family who has read, or even heard of, Frogmorton by Susan Colling. My mum bought a hardback copy from a jumble sale when we were little. It was published in the mid-50s and has beautiful pen and ink pictures by EH Shepard, famous for producing the iconic illustrations for the Winnie-the-Pooh books and The Wind In The Willows.

Frogmorton is also a story of anthropomorphic animals. Timmy, the protagonist, is a tortoise who has fallen on hard times, lives in a bedsit and is painfully lonely. Then one day, shortly before Christmas, he bumps into his old friend Frog, who immediately invites him back to his family seat, Frogmorton, for a country house Christmas. It's only when spring arrives that it becomes clear that Frogmorton itself is in financial jeopardy, and Frog looks to be on the verge of losing his beloved ancestral home. Cue Timmy's help, a chance encounter with a washed-up racehorse and an attempt to win the Gold Cup at Royal Ascot.

The whole thing is touching, charming, oddly wistful and wryly funny throughout. It's also, frankly, a little bizarre, but I never noticed this as a child. I simply loved it. I loved the story, the characters, the 1950s setting, the cosiness, the kindness, the friendship, and EH Shepard's perfect pictures. The fact that nobody else in the entire world beyond my mum and my siblings appears to have read it or is even able to confirm awareness of its existence just made it all the more special for me, then and now.

Unfortunately, Frogmorton was, technically, my brother's book. My mum brought it home for him when I was just a baby, and it's a great favourite of his too. When he left home (I was about 12 at the time) he took his copy with him and I was bereft.

Move forward to my mid-20s. My parents have now fully embraced internet shopping. It's Christmas, and I'm opening my presents. Naturally it's pretty common for most of my presents to be books, so I'm not surprised that my first gift feels like it will be one. But I am surprised when I unwrap my very own copy of Frogmorton.

My parents had remembered that I was sad when my brother rightly took custody of the family copy, and tracked down a copy for me online from a second-hand bookseller. Now I have my own Frogmorton, and every time I look at it, I remember how much I love the book, how completely special and unique a place it holds in my life and my family, and how my parents completely understood.

.jpg)

.jpg)