One of my earliest memories is coming downstairs one morning and seeing that a large red poster had been Blu-Tacked into the window of our front room. I asked my mum what it was and she said it was Labour poster because we didn't want Margaret Thatcher to win the election. When I asked why - it was 1979 and I would have been three at the time, so do forgive me for my ignorance - she said "Because she's a nasty, evil woman."

I was born in 1976; I was studying for my GCSEs by the time Thatcher resigned and I was a grown woman of 21 by the time I got to see anyone other than the Tories win a general election. Consequently, throughout my childhood and teens I could see nothing but the bleakest of futures for the country, with Thatcher playing the part of the ever-present malevolent force behind the destruction of everything my family believed in - rather like Orwell's vision of 'a boot stamping on a human face forever' in Nineteen Eighty-Four. My memories of watching the news as a child (yes, I was the sort of child who watched the news) are a grim mix of dole queues, picket lines and boarded-up factories interspersed with hunger strikes, nuclear weapons and the Falklands, with Thatcher hovering above it all and pulling the strings like some sort of spectral puppet-master.

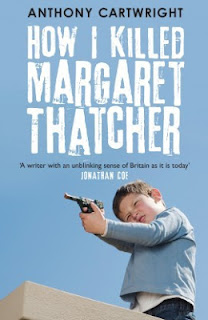

Sean Bull, nine years old at the start of Anthony Cartwright’s Black Country-set novel How I Killed Margaret Thatcher, is similarly haunted by Thatcher. The novel begins with his beloved grandfather punching his Uncle Eric for voting for her; fortunately he doesn’t know Sean’s dad secretly cast his ballot for the Tories too. At first, Thatcher appears to Sean almost as a pantomime villain, her hard eyes and mean voice rarely off the television, but gradually, Thatcherism begins to have a real and tragic impact on Sean’s family life. His male role models rendered jobless and emasculated by the closure of the local steelworks, his mother driven to drink as the mortgage goes unpaid, Sean sees Thatcher as an increasingly malevolent force. And after a horribly traumatic experience in his early teens, and knowing that there is a old wartime gun hidden in his grandfather's shed, he realises that he might just have just have the means to stop her.

I was born in 1976; I was studying for my GCSEs by the time Thatcher resigned and I was a grown woman of 21 by the time I got to see anyone other than the Tories win a general election. Consequently, throughout my childhood and teens I could see nothing but the bleakest of futures for the country, with Thatcher playing the part of the ever-present malevolent force behind the destruction of everything my family believed in - rather like Orwell's vision of 'a boot stamping on a human face forever' in Nineteen Eighty-Four. My memories of watching the news as a child (yes, I was the sort of child who watched the news) are a grim mix of dole queues, picket lines and boarded-up factories interspersed with hunger strikes, nuclear weapons and the Falklands, with Thatcher hovering above it all and pulling the strings like some sort of spectral puppet-master.

Sean Bull, nine years old at the start of Anthony Cartwright’s Black Country-set novel How I Killed Margaret Thatcher, is similarly haunted by Thatcher. The novel begins with his beloved grandfather punching his Uncle Eric for voting for her; fortunately he doesn’t know Sean’s dad secretly cast his ballot for the Tories too. At first, Thatcher appears to Sean almost as a pantomime villain, her hard eyes and mean voice rarely off the television, but gradually, Thatcherism begins to have a real and tragic impact on Sean’s family life. His male role models rendered jobless and emasculated by the closure of the local steelworks, his mother driven to drink as the mortgage goes unpaid, Sean sees Thatcher as an increasingly malevolent force. And after a horribly traumatic experience in his early teens, and knowing that there is a old wartime gun hidden in his grandfather's shed, he realises that he might just have just have the means to stop her.

The novel is narrated entirely by Sean, but Cartwright has him tell the story from both his childhood and adult perspectives, giving us the benefit of that strange mix of uncertain confusion and sharp clarity that tends to come with childhood as well as an adult’s hindsight. It’s hard not to like the younger Sean. He's a bright boy, interested in everything that goes on around him, full of questions and fond of the library, yet at the same time, satisfied with relatively modest comforts: when asked to draw his fantasy ideal home for school, he simply draws his grandparents’ council house in Dudley and adds a football pitch. Far from being praised for what struck me as an endearing and admirable lack of greed, he’s marked down for having low aspirations.

It’s probably fair to say that some of the supporting characters in How I Killed Margaret Thatcher are largely there to represent facets of political opinion or social types. Uncle Johnny, who has left art college under pressure to bring in a wage, is a radical revolutionary socialist with a poster of Bobby Sands; Sean’s grandad, on the other hand, is a conventional Labour traditionalist and the two regularly come to (figurative) blows over their conflicting views. Sean’s father, who works all hours he can to afford to own his own home, is a disillusioned former Labour voter to whom Thatcher's doctrine of self-improvement and ambition appeals. This doesn't however, make the characters unconvincing - far from it, in fact. They are well-realised and three-dimensional, and it's remarkably easy to empathise with them, to understand them, to care about them.

The politics of Anthony Cartwright’s novel aren’t subtle, but then, neither was Thatcherism. I found Sean’s childhood experience of feeling that Margaret Thatcher genuinely and personally hated ‘us’ is convincing and realistic. Before accusations of 'Well, you would say that, wouldn't you' are tossed at me, I'd like to think that even an ardent Tory would at least be able to read this book and come to understand why Sean feels the way he does, even without agreeing with him. Against the political backdrop, a domestic drama is played out as Sean's family's lives, fortunes and relationships change and a close-knit community crumbles. Sometimes funny, sometimes almost unbearably heartbreaking, it's this that gives the novel its real heart.