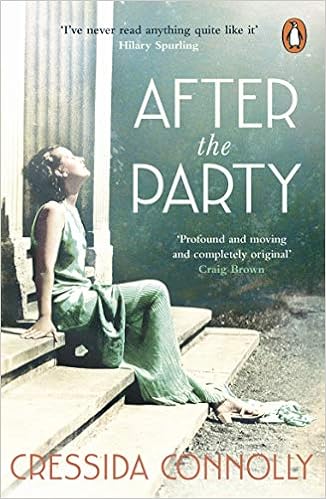

After The Party by Cressida Connolly

It's 1938 and Phyllis Forrester has just returned from the continent with her husband and children. She's looking forward to seeing more of her sisters, Patricia and Nina, and being back in England while her husband designs their new home. Finding herself rather at a loose end and looking for a way to occupy her children before they're sent away to boarding schools - the Forresters are wealthy and Phyllis doesn't, of course, have to work or keep house herself - Phyllis throws herself into helping her sister Nina with the summer camps she runs on the Sussex coast for what initially appears to be a sort of scouting movement. It all seems very jolly - the upper classes recruiting people of all backgrounds to go camping, join in with healthy outdoor activities, get to know new people and listen to inspiring lectures. But the organisation's emblem is a lightning bolt in a circle, and the shirts of their uniforms are black...

It's 1938 and Phyllis Forrester has just returned from the continent with her husband and children. She's looking forward to seeing more of her sisters, Patricia and Nina, and being back in England while her husband designs their new home. Finding herself rather at a loose end and looking for a way to occupy her children before they're sent away to boarding schools - the Forresters are wealthy and Phyllis doesn't, of course, have to work or keep house herself - Phyllis throws herself into helping her sister Nina with the summer camps she runs on the Sussex coast for what initially appears to be a sort of scouting movement. It all seems very jolly - the upper classes recruiting people of all backgrounds to go camping, join in with healthy outdoor activities, get to know new people and listen to inspiring lectures. But the organisation's emblem is a lightning bolt in a circle, and the shirts of their uniforms are black...Cressida Connolly's After The Party is a fascinating novel about, as you've doubtless guessed, the upper class members of Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascists, shortly before the Second World War. Told from Phyllis's point of view, the story switches between the events building up to the war and shorter sections that take the form of an interview Phyllis gives to a researcher as an elderly woman, in which we learn that she has spent some time prison. The party of the title could have many meanings - is it British Union itself? Is it the society soirée that ends in a terrible tragedy for which Phyllis can never forgive herself? Or is it a way of life enjoyed by a certain section of British society that effectively disappeared during the war and never returned?

I have very few criticisms of After The Party, which I found a compellingly thought-provoking read, although I did feel the one incident that Phyllis regards as pivotal in her life, and to which she constantly refers to as the source of terrible personal guilt, is oddly anticlimactic and almost like something from a different novel altogether. That said, it's still a shock, and like the rest of the book, written in way that makes us question our perception of what happens as we view it through Phyllis's eyes.

One of the most unsettling things about After The Party is the degree to which it's possible to sympathise with Phyllis at times, even while finding the British Union of Fascists utterly abhorrent (if you don't find it abhorrent, I've frankly no idea what to say to you). For a while, we can almost see how certain types of people who remembered the horrors of one world war might have been seduced by Mosley's sly promises of peace with Nazi Germany - it was all about peace, Phyllis constantly tells us, peace and looking after Britain's interests rather than intervening in foreign conflicts. But then some of the youth members sprays 'Perish Judah' on a wall and Phyllis ... does nothing. She doesn't 'want anyone to perish', she says, but she's more concerned about the vandalism. Cressida Connolly writes Phyllis very cleverly: she's easily one of the most likeable characters in the book in every respect (not that she has much competition - this book is absolutely full of fascinatingly horrible, over-privileged posh people) and she's also infuriatingly passive.

Is Phyllis just swept up in a movement that makes her feel she belongs for the first time in her life, going along with her peers for the sake of making friends without really understanding the implications? Can she truly be a 'real' fascist? Or is it we, the readers, who are being duped by her haplessly personable manner? It's this question that, for me, lies at the heart of After The Party, and it's a dilemma that genuinely preyed on my mind over the few days it took me to read it. Personally, think it's a question that's answered pretty decisively by the end, but some readers might feel differently.

Comments

Post a Comment